Forging tomorrow’s technology

History always has a tale to tell. Looking back on more than 30 years of HUGIN, we talk to Kongsberg Maritime’s Jon Kristensen and Per Espen Hagen about their lifelong careers with our autonomous underwater vehicles.

-

Text:Marketing & Communication Department

Photo:Photos ©FFI

-

Gunvor Hatling MidtbøVice President, Communications

You may think that working on a project for more than 30 years would jade some people’s enthusiasm, but for Kongsberg Maritime’s Jon Kristensen and Per Espen Hagen they are still as excited about the further potential of the HUGIN autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) as they were when they first started working on the technology back in the early 1990s.

The launch of the new HUGIN Edge is testament to that passion and they believe the new mission-goal planning software currently being developed will be a game changer too for the AUV sector.

However, back in the 1990s Jon, Software Team Manager, Marine Robotics, described the first HUGIN prototype as a very ‘dumb animal’. It had originally been developed by the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment (Forsvarets Forskningsinstitutt – FFI) as a way of testing and developing its new seawater batteries and it partnered with Kongsberg Maritime to provide acoustic navigation and communications capability.

Senior Principal Engineer Per Espen, who transferred from FFI to Kongsberg Maritime to join the AUV team in 2008, explains the issue with this new battery technology at the time: “The problem with a seawater battery is that it needs oxygen to create electricity and therefore requires a constant flow of seawater through the system. FFI had an idea of moving the battery through water instead and that’s how the idea of building an AUV as a platform for testing came about in the very early 1990s.”

From humble beginnings

The prototype HUGIN was a very simple AUV with a minimal payload and couldn't do much more than go in a straight line underwater – but it could do so for several days, which was unheard of at the time. However, while the first trial run from Norway towards Denmark was successful, there was a reluctance from both the military and the offshore oil and gas sector to spend millions of pounds on an unproven ‘science fiction’ technology.

Despite this, FFI and KM persevered and, with improvements in battery power, navigation and sensor reach, in 1995 a partnership was formed with the Norwegian state oil company Statoil (now Equinor ASA) and NUTEC (now NUI), a subsea operations and dive support company, to develop a state-of-the-art AUV for seabed surveying. This partnership thus involved the complete supply chain, from the technology and product developers, via the system operators, to the end customer of the data products.

Statoil was so satisfied with the project’s progress that in 1997 they urged FFI, KM and NUTEC to use the first HUGIN vehicle in the Åsgard gas pipeline survey – more than a year before the planned completion of the HUGIN system. Despite system limitations and teething problems, the survey was a major success, and was instrumental in helping Statoil keep to its survey schedule.

The first commercial contract came in 1999 from a US-based offshore survey company called C&C Technologies (which became part of Oceaneering), which was an existing customer of KM’s multi-beam echosounders. This was a joint R&D project between KONGSBERG, FFI and C&C to develop a 3,000 metre-rated HUGIN AUV with integrated sidescan sonar and multi-beam echo sounder.

Jon says: “Our contract with C&C Technologies was to deliver a vehicle that had added navigation algorithms so the HUGIN could follow a waypoint route. The vehicle completed a planned three-year mapping project in the Gulf of Mexico in just eight months. After this breakthrough, we got more contracts and then we started to build up our team at the HUGIN development centre.”

Per Espen says: “The quality of our acoustics – providing a ‘virtual tether’ – was one of the main drivers for our success through the 1990s and into the 2000s. Tracking the position of the HUGIN from a surface ship gave customers the confidence that the systems were reliable and that the AUV could execute missions.”

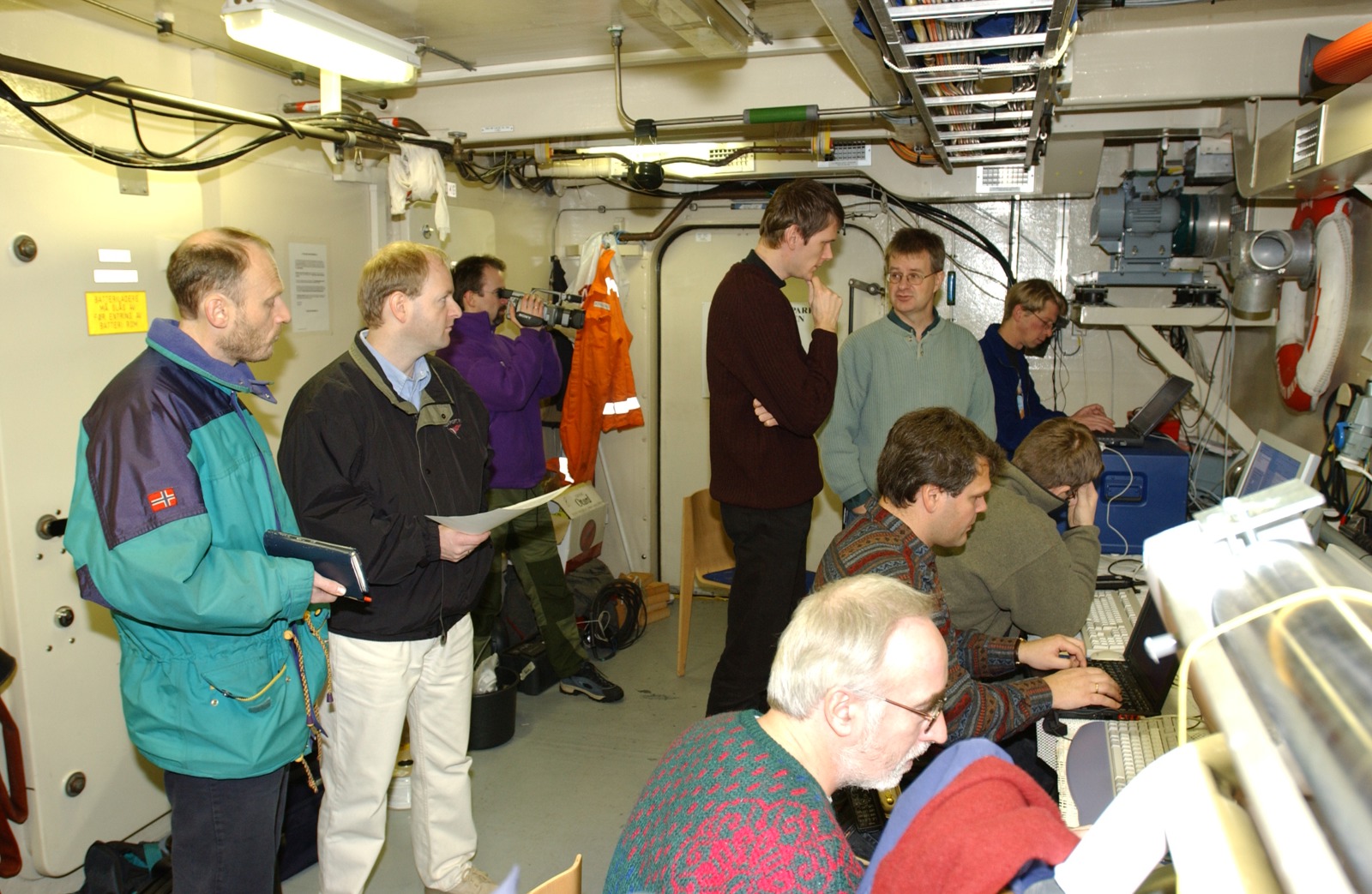

In 1997, Statoil conducted a trial onboard the M/S Seaway Commander to assess how well a HUGIN AUV could map the seafloor compared to a traditional survey carried out with an ROV controlled via a cable from an operator ship.

After five days of intensive trials, the HUGIN proved its worth, mapping the seabed faster and with the same quality as the ROV.

Pictured here (far right in white t-shirt) are Jon Kristensen, and next to him on his right is Bjørn Jalving who is now Senior Vice President Technology in KM, Sensors and Robotics Management. Standing at the back is Nils Størkersen, who has been Director of Research at FFI since 1999.

Looking back on the project, Jon believes the big milestones in the HUGIN’s development came from step changes in battery technology and KM’s navigation system. He explains: “The batteries allowed the AUVs to stay down longer and that meant they were more economical to deploy. With the development of new lighter and smaller lithium polymer batteries, which could work under ambient pressure, this meant you had more power and, just as importantly, more space in the vehicles for bigger sensor payloads.

“But I believe our navigation system, which we have been continuingly enhancing and developing, was a game changer also, and particularly our expertise in acoustics, which has enabled all our sensors in each vehicle to work efficiently together without interference or compromising data gathering.”

HUGIN Family

Meet the HUGIN family

The HUGIN family of AUVs has expanded in recent years with the introduction of the HUGIN Superior, which has a large payload of sensors with enhanced autonomy, and the HUGIN Endurance, with 15 days of operational life which can execute autonomous shore-to-shore missions over long ranges. And, of course, the launch of the new HUGIN Edge in 2022, which represents another step change in technology, employing a radical new low-drag design but also enhanced capabilities through its goal-based mission planning software.

This is what excites the KM AUV team, as Per Espen explains: “Goal-based mission planning is the next step in the autonomous development of the HUGINs. This is something we've talked about and wanted to do for more than a decade, and it's finally coming to fruition.

“With goal-based planning, the idea is to provide the vehicle with a higher understanding of the mission plan. You set the survey goals – survey this specific area to this level of data resolution or detection, at a certain level of confidence, etc. – and the AUV itself will determine how to do this most efficiently.

“There are two very big advantages to this: first of all, you alleviate the operator from complicated and tedious planning – and expensive training – as the process is now totally automated; and secondly, and even more important, is that the vehicle can change the plan during the mission if it encounters a situation that does not allow it to meet the mission goals. So, if during a mission it determines that it is getting a shorter range on the sonar than expected, it will adjust its path to move the survey lines closer – so it basically thinks for itself.”

“FFI has tested and demonstrated goal-based mission planning on AUVs for a number of years and we have been collaborating with them to develop a commercial software product which we will be able to deploy on the HUGIN Edge soon.”

Find out more about HUGIN Edge here.