The hunt for Flight 447

On a sandy bank, 4000 metres under the surface, the wreck of Air France Flight 447 was found. This is the story of REMUS 6000 – the vessel which helped solve the mystery of the tragic accident which took 228 lives

-

Text:WIL S. HYLTON AND OVE RONNY HARALDSEN

Photo:SYLVAIN PASCAUD

-

Ove Ronny HaraldsenGroup Communication Manager

Late afternoon on the 3rd of April finds the expedition vessel Alucia out on the rough seas of the South Atlantic, with a storm forecast. On the aft deck sit the crew, huddled close together in their rain coats and sou’westers, as they gaze out over the choppy seas.

They are keeping a careful watch out for a yellow reconnaissance submarine which has 15,000 images onboard. However, the submarine reaches the water’s surface just as the storm breaks, and with winds of 30 knots and metre-high waves crashing over the aft, it is deemed too dangerous to haul in the submarine.

So all they can do is watch and wait. Over the past eight days, the Alucia has been sweeping over the area of the Atlantic known as LKP, or Last Known Position for Flight 447, the Air France plane which disappeared in June 2009, just about halfway between South America and Africa.

Over the past two years, three other search teams have sailed out here to try and find the wreck. This is the Alucia’s first attempt. The ship carries three autonomous subsea vessels, type REMUS 6000 from Hydroid, one of Kongsberg Maritime’s subsidiaries.

AN IDEA IS BORN

Chris von Alt is the man who knows the REMUS 6000 best. He is currently Managing Director of Hydroid, located in the town of Pocasset on the east coast of the States. The REMUS 6000 originated from the great idea that autonomous technology could provide drastic improvements in the efficiency of operations to chart deep seas. To find the wreck of Flight 447 would be all the proof they needed.

“Traditionally, a submarine is towed behind a ship on a cable. This creates a lot of resistance in the water and there is significant momentum in the cable. The ship cannot sail all that quickly and it can take several hours to turn the ship, cable and submarine. An autonomous submarine, or what we refer to as AUV, is up to ten times more efficient. It is quicker, turns more rapidly and takes better photographs. If a ship has three REMUS 6000 submarines, then you improve efficiency by a multiple of thirty,” explains Chris von Alt, going on to say:

“If any subsea vessel could find the wreck of Flight 447, it had to be the REMUS 6000.”

THE FIRST SONAR IMAGES

Out on the waters of the South Atlantic, the three subsea vessels continue to sweep over the seabed, running 20-hour shifts before resurfacing to deliver their sonar images to the scientific team onboard Alucia. The data is investigated 24-hours a day, working 12 hour shifts.

So far, they have not found the wreck, but the day before, one of the researchers pointed at the screen and asked “What about this?” Immediately, the level of tension was practically tangible onboard.

Everyone knows what is at stake. This is not just an operation to scan the Sargasso seabed or take water samples to measure salt content. This is a question of the families of 228 passengers, waiting expectantly for results. The search had already taken two years and cost more than USD 25 million. A further USD 12 million had been set aside for the Alucia that year.

the aircraft wreck. “This is a powerful confirmation of the value of REMUS 6000 as a tool,” comments Chris von Alt from Hydroid.

If the Alucia with its REMUS 6000 could not find the wreck, it would most probably never be found. As leader of the expedition, Michael Purcell is both a colleague and the boss. As he observes the unclear images on the computer screen, he knows they have found something that has not been made by Mother Nature.

It is too long and straight to be geological. It does not resemble anything you would normally find on a seabed. On the other hand, Michael Purcell is painfully aware of how disappointing it would be if it turned out not to be the wreck.

A RISK WORTH TAKING

More than 15 years have passed since Michael Purcell worked as a mechanical engineer on the team to develop the REMUS. The team leader was Chris von Alt from Hydroid. At that time, both men worked at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute – the research foundation which found the wreck of the Titanic in the 1980s.

In 2001, Chris von Alt was part of the team to set up Hydroid, and the new company was awarded exclusive rights to produce and further develop REMUS. In 2008, Hydroid was acquired by KONGSBERG, and REMUS is now one of a range of autonomous subsea vessels for different sea depths.

The REMUS 6000’s list of merit is long. Last year, REMUS 6000 was used to rechart the wreck of the Titanic. In 2009, it took part in the exploration for the wreck of Amelia Earhart’s aircraft – the American flying pioneer who disappeared over the Pacific in 1937 when attempting to fly around the globe.

“I have worked with this technology for 20 years now. The high profile assignments we have received are confirmation that the ideas and technology we gambled with 20 years ago actually work. We have created a system out of nothing, and it has proven to be of significant value. It’s like placing a bet on a horse, isn’t it. People will come up to me and say: ‘You were smart. You bet on a good horse’.”

IMAGES FROM THE DEEP

As Michael Purcell gets the REMUS 6000 ready for a new 18-hour shift on the seabed, he whispers to one of the other researchers:

”I’m 95 percent sure that it’s the plane, but God help us if it’s not – then we’ve got a long two and half months ahead of us.”

The submarine descends into the deep at 22.45. At two o’clock in the morning, Michael Purcell is still wide awake in his cabin. He takes out his diary and writes: “Tired but not sleepy. May have found the plane today. It’s all a bit hectic.”

Four hours later, Michael gets up with the sun and makes his way out to deck in the morning together with the crew, watching the REMUS 6000 as it bobs on the water’s surface. Just after 13.00, they are able to haul the vessel onboard and connect the two thick cables which upload the data to the computers in the expedition’s control room.

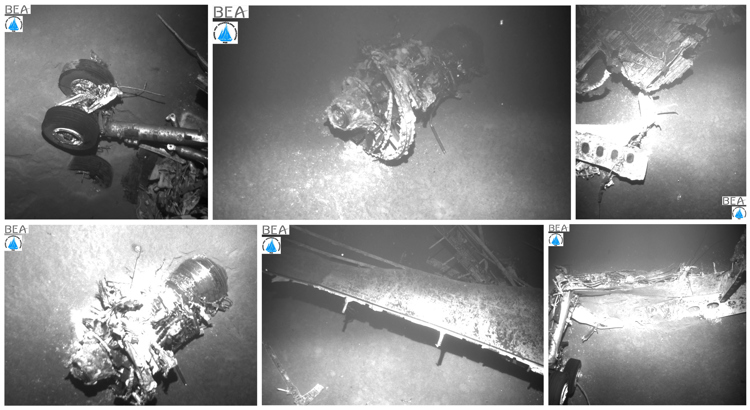

They close the curtains in the control room to prevent other non-scientific expedition members from peeking in, and pull out the cable for satellite connection, so that no-one can leak the news. Then they crowd around the computer as the first images of Flight 447 appear on the screen: engines, landing equipment and parts of the fuselage stand out unmistakably on the seabed.

had been found on a sandy bank, 4,000 metres under the surface.

CLOSURE FOR THE FAMILIES

That same evening, the news of the find of Flight 447 is on every headline across the globe. Chris von Alt is at a sales exhibition in Southampton when he is notified of the find. Keen to learn more, he logs on to the Internet and opens several websites which are monitoring the search day by day. He reads blogs, studies sonar images, rings colleagues. He wants to know everything.

“We knew that the REMUS 6000 was set for its last attempt to find the fuselage. The team had set aside 90 days for the search operation. And they found the plane after only eight days. This is a substantial confirmation that REMUS 6000 is a valuable tool in many ways.”

“How is that?”

“This brings closure for those who lost their loved ones on the flight. They can gain a closer understanding of what happened and they now know where they are. I hope the find can help shed light on the sequence of events, so that we can prevent similar accidents from occurring.”

“How do you feel personally about Hydroid’s product making such an important contribution?”

“I feel a certain sense of pride that the system has proven how well it works – that REMUS 6000 can generate such important information and can help all these families.”

A MYSTERY SOLVED

Late April, the cable ship ‘Ile de Sein’ arrives at the site where Flight 447 went down. The crew onboard has a detailed map of the find, created using the data collected by REMUS 6000.

On 1 May, the first black box is lifted up to the surface, using a mini-submarine with grapplers. Two days later, black box number two is brought to the surface and transferred to a fresh-water container for transport to the investigation team in France. Barely two weeks later, the news that everyone has been waiting for is announced: The content in the black boxes can be read, despite almost two years of vast pressure on the seabed.

Back home in Cape Cod, Michael Purcell is writing his report when he hears the good news. However, the pleasure at finding the wreck will always be a bitter-sweet memory for Purcell and the rest of his crew who joined him on the expedition in the South Atlantic.

As the researchers onboard the Alucia scan the first images of Flight 447, they see more than just the landing wheels, engines and a wing. They also see the missing passengers, down on the deep sea bank at the foot of the mid-Atlantic ridge.

An uncomfortable silence spreads over the ship. These images will remain with them forever. It is an unpleasant mix of emotions, sadness combined with happiness at finding what they were searching for. We ask Michael Purcell how he feels about his contribution to finding Flight 447.

“I think the greatest reward is that the families can now find the peace to continue with their lives,” he concludes thoughtfully.

The article is based on the report entitled «What Happened to Air France Flight 447?» by Wil S. Hylton, printed in the New York Times Magazine, and interviews of Chris von Alt and Michael Purcell. The article has been edited by Ove Ronny Haraldsen.