Yet understanding the submerged ice face is critical for predicting sea level rise and modeling climate change.

That’s where sound comes in.

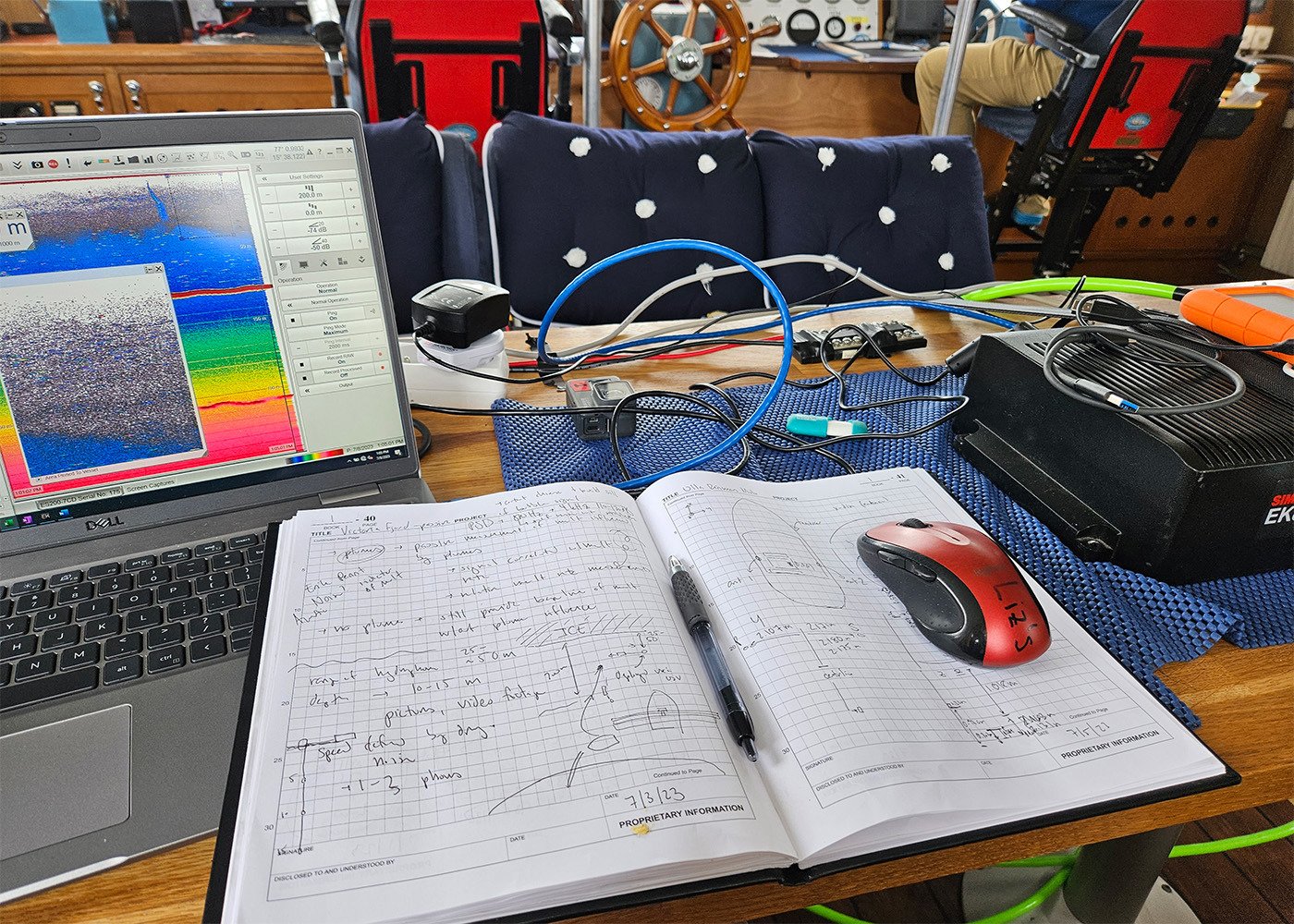

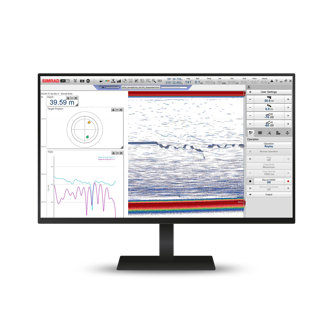

Led by Professor Elizabeth Weidner of the University of Connecticut, the research team turned to acoustic technology for a breakthrough. Using the KONGSBERG EK80 broadband echo sounder system, they sent sound waves toward the glacier from a safe distance and analyzed the echoes that returned. By sweeping the sonar across different angles and frequencies, they were able to map the underwater ice wall and determine its shape and physical properties.

One of the key innovations in the study was the use of split-aperture processing, a technique that allowed the team to pinpoint the exact position and tilt of the glacier’s submerged face. This level of detail is crucial for understanding how glaciers melt, how icebergs form, and how ocean water interacts with glacial ice – all of which are vital pieces of the climate change puzzle.

“The underwater part of a glacier is really hard to study because it’s dangerous and constantly changing,” said Professor Weidner. “Using sound waves, we were able to safely collect detailed data without getting too close. This helped us figure out the shape and angle of the ice below the surface, which is important for understanding how glaciers melt and break apart.”