AIS base stations for a wild location

The Norwegian Coastal Administration (Kystverket) and KONGSBERG have been working to develop, install and maintain AIS base stations that will help monitor and manage maritime traffic around Svalbard, while dealing with hazards like extreme cold, powerful gales — and polar bears.

-

Text:Marketing & Communication Department

Photo:©Fraser Morton, Far Features

-

Gunvor Hatling MidtbøVice President, Communications

When you’re trying to introduce new technologies to a sensitive ecosystem, you have to be aware of some of the difficulties you might encounter.

For Kystverket (Norwegian Coastal Administration) and KONGSBERG, working to improve marine traffic monitoring and management around Svalbard, that meant thinking about extreme conditions and local wildlife — which includes a reasonably significant polar bear population.

Safety on the seas

AIS (Automatic Identification Systems) Norway, operated by Kystverket, provides a continuous overview of ship traffic along the Norwegian coast. Information from on-board AIS transponders about the identity, position, speed and course of ships around Norway is captured by 70 base stations along the coast, and by four AIS satellites.

“On Svalbard it's very important to leave as small a footprint as possible — nature there is very vulnerable and there are strict regulations for what we can put in place. That’s the good thing about these new stations. They make it possible to do what we need to do and respect the local environment.”Arve Dimmen, Director Maritime Safety, Kystverket (Norwegian Coastal Administration)

“We started developing base station coverage on the Norwegian mainland in around 2004/2005,” says Arve Dimmen, Director Maritime Safety, Kystverket. “Over the years, that has become extremely valuable for maritime safety, traffic statistics and development.

“At Svalbard we had very limited coverage, and in recent years traffic in the area has steadily increased as a result of tourist cruises and fishery activity moving further north. We needed to expand coverage to reach this area as well.”

That meant installing AIS base stations on the Svalbard archipelago, which sounds simple enough. This was a project, however, that would throw up some quite extraordinary challenges.

It’s home to a huge population of birds, along with red-listed mammals such as walruses, harbour seals and polar bears. And, not least, it’s subject to extreme cold, gale-force winds and six months of darkness every year.

“When I looked at pictures of Svalbard, all the antennas and everything were covered in ice,” says Harald Asheim, Project Manager at Kystverket. “It was so thick it looked like cauliflower! I thought ‘how can we solve this one?’

“I spoke with the Meteorological Institute. They said that ice was because of the height — if you install antennae too high, they ice up. If you install them too low, you get problems with the polar bears.

“Bears are 700 kilos of muscle, and very curious. They bite everything. We need to put the stations high enough to be safe from bears, but low enough to stay clear of ice.

“Then we had to think about the communication issue. There's complete silence around Svalbard, no communication at all. If you have a cell phone with you, it's dead. And there’s no regular satellite coverage. We need instant data. So, how do we deal with that?

“The KONGSBERG team came up with an idea — we let the base stations talk to each other. Now we know if we put stations at a certain height and let them talk to each other, we get good coverage. That was the initial structure of the idea.”

-

AIS satellites0

-

metres above sea level385

-

per cent of the surrounding ocean is protected70

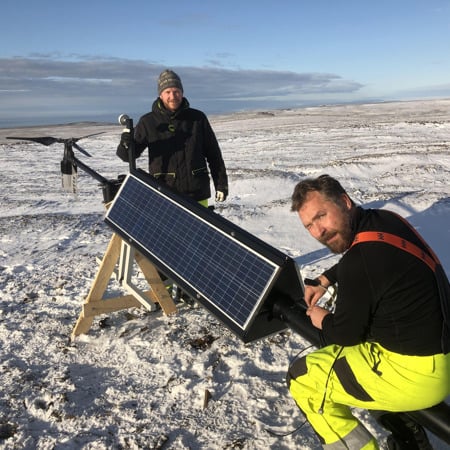

“We were playing with the idea of making a base station with a self-contained power source,” said Cato Eliassen, Product Manager with Kongsberg Seatex. “The first idea was for solar panels, but then we had to think about how it would survive during the winter.

“We thought about putting in a lot of batteries to charge during the summer and survive the winter, which was a good idea, but meant we would need a lot of batteries. We then started looking into wind turbines.

“We spoke with the Svalbard authorities, the Meteorological Institute, telecommunications company Telenor, and aviation company Avinor, which runs the airport — they all had experience of using turbines, but none of them were generating the kind of power we’d need.

“After playing with the idea for about a year, and trying various turbine modelling exercises, we finally discovered a new turbine in the United States that had blades coated with silicon that reduced the ice problem. That’s what we use today, supported by solar panels, and it’s working perfectly.”

The next problem to consider, Cato explains, was what to do with the excess energy created by the turbine. With no way simply to turn them off, the energy supply could exceed demand once the station’s batteries were fully charged. That extra energy had to go somewhere.

“We’re one of only a few manufacturers of AIS base stations in the world, with stations all over the world, including Norway. Supply was not the tricky part of this project. The tricky part was delivering stations that would work on these sites.”Cato Giil Eliassen, Product Manager, Navigation and Infrastructure, KONGSBERG

The team came up with the idea of using it to heat the base station cabinet. “If the cabinet gets very cold inside, the capacity of the battery decreases,” says Cato. “This way we can keep it above zero degrees. The rest of the power goes into a kind of oven outside the cabinet, preventing extreme build-ups of ice.”

ADVENTUROUS INSTALLATION

“It's very difficult to get the equipment in place, because we want to have it 200-300 metres above sea level,” says Harald Asheim. “And each base station weighs between 600 and 700 kilos. We had to think about how we could install it without any mechanical help.

“The idea was to install in modules, with two technicians installing each module — we’d fly in three or four modules separately, then the engineers could install it.

“After we’d tried that we talked with the pilots, and they asked if we could deliver everything in one installation to reduce the risks of flying in these wild locations. For the next base station we put it in the right configuration, flew it up in one piece, and the technicians put in the batteries and wires and placed it into the earth.”

No small feat in itself – the archipelago’s soil is very loose, so the stations need to be secured between one and one and a half metres down. Maintenance teams are often working in isolation and in freezing conditions.

“The station sites are 200 to 400 metres above sea level, and it's not easy to walk up these hills,” says Cato Eliassen. “Our teams need to be taken up there by helicopter and left. Two engineers and a guard with a gun – because otherwise you could easily become dinner for a polar bear.”

“When we’re working we’re occupied inside a cabinet and we don't look behind us. It’s much better to have one person taking care of safety so we can get on with the work!”

Ørjan’s fellow engineer Rune Simonsen remembers their first trip with a guard. “We were flying out to Hinlopen, and just before we entered the installation zone, we spotted eight or nine bears. The helicopter couldn’t land with us, because the ground was too soft. We had to work without them, knowing there were eight or nine bears around.

“They were two or three kilometres away, so it wasn’t too bad. But we concentrated pretty hard on getting the installation done and getting away!”

Despite the dangers, and the freezing conditions, and the incessant wind, the two men love their job.

“It’s really pretty cool,” says Ørjan. “Every trip on the helicopter, jumping out onto the snow, it’s kind of special. You don’t get used to it.”

Rune agrees. “We get to experience something that most people will never get to see,” he says. “It’s actually a real privilege to be part of it.”

“It was very important in Svalbard to leave as small a footprint as possible,” says Kystverket’s Arve Dimmen. “Nature there is very vulnerable, and there are strict regulations for what we can put in place.

“One of our main tasks here has been to have very good cooperation with the local authorities, making sure that we understand the restraints and use their knowledge to decide the particular placement of units and how they will fit into the natural architecture.

“With this new type of station, it's actually possible to do all that. I think it’s an interesting development for many other places in the world where we want to have AIS capability, but without leaving a big footprint. And that’s a good thing.”

Arve Dimmen , Director Maritime Safety Kystverket (Norwegian Coastal Administration)